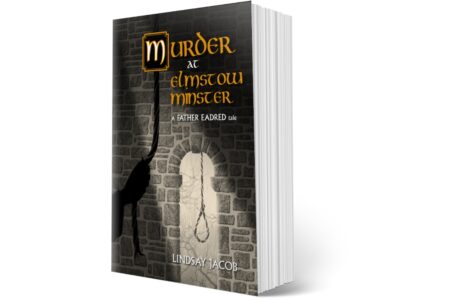

In my recently released novel, Murder at Elmstow Minster, set in a community of nuns in the 830s, there is an Anglo-Saxon trial by ordeal. What were such trials? When were they applicable. How did they attempt to identify whether a person was innocent or guilty? They may seem completely bizarre to the modern Western mind but when we travel back to an age when God was acknowledged as the ultimate judge, then they make more sense. Yet this does not mean they were without problems for the Anglo-Saxons – far from it. I ask readers of my novel to assume the existence of the spiritual world (even if you do not believe in it) and to let the barrier between secular and sacred dissolve, for then you will get closer to the mind of the Anglo-Saxons.

What Were Trials by Ordeal and How Were They Interpreted?

If someone were accused of a crime but claimed to be innocent then the troublesome matter of proof became important. Ordeals were a means of obtaining proof – but they were a last resort. They were a direct call on God to issue judgement and were performed within a strict framework by the Church. While their ostensible purpose was not to punish, they did inflict shocking pain and a possible lengthy period of disability for the accused.

The two most familiar and heavy duty ordeals were by hot iron or hot water. In the former, the accused had to carry a bar of red hot iron over a distance of nine feet. In the latter he/she had to pick out a stone from boiling water. The hand was then bound and sealed for three days. When the bindings were removed, a clean hand demonstrated that God had shown the accused to be innocent but an unclean hand showed they were guilty. Punishment followed.

However, if the accused was already known to be of particularly bad character, or the crime was heinous to the community, then the ordeals became more exacting. A triple ordeal involved carrying a heavier bar of iron or plunging the hand and forearm deeper into boiling water (Lambert, T., 2017: p257).

The tricky question is how the state of a hand after it had endured an ordeal bore witness to guilt or innocence. Scholars suggest that God’s determination was frequently confusing to Church officials. Were they meant to see a hand that was either clearly healing, rather than festering; or a full-on biblical miracle? (Forbes, H.F., 2018: pp270-71).

There was then the issue of punishment for those who failed their ordeal. It did not necessarily mean execution. It could be a fine, slavery or maiming. The severity of punishment differed according to crime and across regions and time (Forbes, H.F., 2018: pp261-2). The confusion in discerning God’s will and in determining how this translated into punishment were troubling for the Anglo-Saxon mind, and not just to the accused. It was a process open to much subjectivity and doubtless also manipulation.

If we look briefly at the Anglo-Saxon approach to crime, the place of ordeals becomes clearer.

Anglo-Saxon Approach to Crime

Dealing with crime in the Anglo-Saxon period differed in important ways to the approach with which we are familiar today. There was no police force to keep the peace and to enforce law and order, and no prisons. While the king promulgated law codes and became increasingly active over the Anglo-Saxon period, the maintenance of a peaceful and ordered kingdom was essentially the responsibility of all free men and women from the king down. It proved to be broadly successful, although hardened and powerful criminals, then as now, gamed and abused the system.

As far as we know, in the overwhelming number of cases, a person accused of a crime owned up and faced the consequences. To do otherwise would invite community censure and the risk of physical retaliation from the injured party and his kin, and this was generally lawful, so long as it was proportionate. If a person denied an accusation then the issue of proof took centre-stage. If the defendant was of good character with a good record, he was required to bring forward a specified number of ‘oath-helpers’, who would swear that his word was good. Should this be accomplished, he was considered innocent. This was quite acceptable in a small-scale society, where a person’s character and behaviour was known. It also provided a disincentive to spurious accusations, as the tables then turned on the accuser. For much of the Anglo-Saxon period, however, the system’s weakest spot was how to deal with hard-bitten, violent criminals, especially those backed by strong kin, as it was a fearsome challenge to confront them.

Crimes against Individuals: An understanding of Anglo-Saxon poetry or of law codes demonstrates that it was a culture in which personal honour was a paramount ideal. A second pillar was a concern to maintain a stable, Christian community, understandable in a small-scale society dependent on cooperation and God’s benevolence.

An affront against a person’s honour needed to be addressed, and hopefully in a way that did not trigger a chain reaction of retaliation. In most cases, this was achieved by use of a precise scale of compensation payments applicable to an exhaustive list of grievances, whether these involved stealing, damage to property, physical injuries or even killing. The scale reflected the hierarchical nature of Anglo-Saxon society. Thus, crimes against noblemen required appreciably greater compensation from the perpetrator or his kin than crimes against ordinary freemen. For most crimes, there was room to negotiate a settlement – owning up and paying less than the full extent of compensation.

As Lambert argues in his excellent book on Anglo-Saxon law and order, the guiding principle behind the level of compensation was not the physical cost of the crime but the cost to the victim’s honour. A person’s wergild was the price of a person’s life, which a killer or his kin had to pay. Commenting on King Aethelberht of Kent’s law code:

‘The actual harm done to a freemen by physically binding him is negligible, yet the required compensation of 20 shillings makes it the equivalent of a serious physical injury: a broken jaw, a chopped-off thumb or an impaled abdomen. Likewise, though violent castration is undoubtedly horrific, it cannot actually be three times worse than death, as the triple wergild specified in compensation for it would suggest’ (Lambert, T., 2017: pp35-6).

It was the responsibility of the aggrieved person or their kin to bring the charge and, for much of the period, it was up to them to organise a forceful response if the guilty party did not accept their obligation to pay compensation. Otherwise, their honour would be tarnished. This does not say that they were without support – their community had a (theoretical) responsibility to cooperate in hunting down and bringing a felon to justice. Also, an individual who refused to pay lawful compensation, or who denied an accusation and then failed to have his oath supported, had to face a higher (and often more painful) standard of proof if they were accused of further crime.

Crimes against the Community: Crimes against individuals could be addressed by compensation and the threat or reality of physical retaliation. The victims generally managed these without much, if any, action by the state for a good deal of the Anglo-Saxon period. It was a different scenario if the crime had broader implications. Such crimes included religious offences that could bring down divine wrath on the community and theft. Lambert argues that a thief’s modus operandi of secrecy posed a serious community threat:

‘… thieves caused harm not just to victims but, through their secrecy, to entire communities, weakening communal solidarity by sowing suspicion among neighbours. Allowing thieves who were caught simply to compensate their victims in proportion to their loss was sufficient neither to deter future thefts nor to address the social harm theft caused’ (Lambert, T., 2017: p350).

It follows that if secret theft of material things was a significant problem for Anglo-Saxon law and order, even more so was secret theft of another’s life. To have an anonymous killer at large within one’s tight-knit community was then, as now, catastrophic. This is one of the main themes of my novel, Murder at Elmstow Minster. The minster is torn apart by fear. Crimes against the community involved wider punishments – from higher levels of compensation paid to the king (as representative of the community) through to maiming, slavery and execution.

Increasing Stringency of Proof

Over the Anglo-Saxon period, the requirement of proof hardened against those who had proven dishonourable. There was a number of circumstances when a more stringent level of proof than an oath was enforced. Importantly, this did not include a person who had previously committed venial crimes, owned up and paid the required compensation. It did include people whose oaths had been shown to be suspect in the past by failing to bring forward the required number of oath-helpers. This in itself was a disincentive to vexatious accusations.

In a society where personal honour was extolled, lying on oath was not only considered reprehensible; it was an affront to God and would call down divine punishment, if not in this life then in the next. Thus, most folk would be reluctant to swear incorrectly that the accused’s oath was good, for to knowingly perjure themselves was to put their own standing, let alone their souls, at risk. Levels of proof also increased for those who had previously sought to evade their compensation requirements, and those accused of secretive crimes – theft and murder.

It was these categories of felons that were obliged to endure ordeals for they had lost the right to be treated as honourable men and women. They had committed perjury, failed to meet their obligations, or had harmed the fabric of society. Secretive thieves and murderers, who were subsequently found guilty by any of the methods of proof, were in for a rough ride, although not necessarily execution. Although thieves caught in the act or with their spoils in hand could be lawfully killed on the spot (Lambert, 2017: p255).

Conclusion

We should not imagine that the incidence of oaths and ordeals was rife. What evidence we have suggests that most wrong-doers owned up and paid compensation (in total or a negotiated portion), accepted their punishments, or tried to evade justice through recourse to the protection of powerful kin or supporters. Lambert, drawing on Patrick Wormald’s study of legal cases, finds that ‘actual instances of oaths being sworn or ordeals taking place are rare (Wormald, in Lambert, T. 2017: p283). There are good, practical reasons for this. In a period of ubiquitous belief in God, perjury would bring down God’s judgement. Ordeals were also shockingly painful and potentially disabling. They would have a significant impact in an age when for many, one’s hands were one’s livelihood. We can imagine that the implications of a failed oath or ordeal were incentive enough for most felons to try to avoid them.

It was clearly preferable to the Anglo-Saxons that a person admitted their guilt or were caught red-handed, and that recourse to establishing and interpreting proof could be avoided. Secretive crimes – theft and murder – were thus problematic, and the difficulty of discerning God’s will through ordeals made them even more troubling. It is in these trying circumstances that a young priest, Father Eadred, in my novel, Murder at Elmstow Minster, finds that he has a gift for uncovering the truth. It proves to be a double-edged sword.

(All photos taken by author)

References

Forbes, H.F., (2018), Making Manifest God’s Judgement: Interpreting Ordeals in Late Anglo-Saxon England, in Naismith, R. and Woodman, D, A. (eds.) Writing, Kingship and power in Anglo-Saxon England, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Lambert, T. (2017) Law and Order in Anglo-Saxon England, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Wormald, P., Charters, Law and the Settlement of Disputes in Anglo-Saxon England, repre. in and cited from Patrick Wormald, Legal Culture in the Early Medieval West: Law as Text, Image and Experience (London, 1999): pp289-310.

Pingback: Anglo-Saxon Monastic Decay - Father Eadred