Those familiar with Anglo-Saxon history or literature will know the term, ‘hearth companions’ or ‘hearth group’. Although its meaning changed over the Anglo-Saxon period, at core, it is wonderfully redolent of Germanic aristocratic culture. A group of chosen warriors fiercely loyal to their lord (king, prince or noble), often unto death. They were mutually supportive in war and peace, doing their lord’s bidding, courageous, watching each other’s backs, giving and receiving gifts, sharing companionship around a common fire, feasting, drinking, telling time-honoured tales of great warriors and feats of arms and also joining to mourn lost comrades.

Too good to be true? Most of these evocative images come from the few examples of heroic Anglo-Saxon poetry that have survived the attrition of time. Such poems were never a straightforward reflection of reality but were texts loaded consciously and unconsciously with political, cultural, religious, moral and psychological messages, woven into beautifully artistic creations. What we have must be a very small proportion of heroic poetry. Not only because so much written material has been lost but because what survives comes from the conversion and Christian periods and there would be a considerable volume that was only transmitted orally, especially from the pre-Christian period.

A hearth group evolved from the early days in the formation of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, when a leader surrounded himself with a trusted band of men, who acted as his guard and core of the armed men he could call upon in times of war. They were the final enforcers of their lord’s bidding. The concept is not unique with many ancient societies developing a crack troop of warriors that bonded with their leaders.

This article looks at what we may learn of the relationship between a leader and his hearth group from heroic poetry and other information available to us. Does this form of poetic expression provide insights into the pivotal and sacred nature of kingship? Does it reflect the importance of maintaining arms, trust and esprit de corps in a violent, uncertain, hand-to-hand world? Texts that demonstrate for the loyal and courageous that their names will live forever, and to those who flee the challenge that their names will be reviled until the last days? Does it commemorate valour in complex artistic, written and recited imagery, rather than through stone monuments?

Or is it a devious part of ruling class culture – a romanticized autobiography extolling the virtues of blind loyalty to those in charge? And where does the emerging Christian faith come into it? Is the concept a celebration by a conservative elite of pre-Christian warrior bonding – or does it point to a yearning for an eternal Lord? Does the poetry ennoble and consecrate the values of a bunch of honourable fellows or is it a smokescreen for indulgence, privilege, violence, bullying, theft and womanising by a powerful and brutish secular elite? Five elements seem to combine in the depictions of companions of the hearth – the king, the warrior, the gift, the hearth and the grave. Read on ….

The King

An Anglo-Saxon king had several core roles: maintaining the favour of the gods (after conversion, this was the Christian God); defending the kingdom against external aggression; and maintaining internal peace. The latter role probably developed gradually as monarchs saw a greater role for themselves in maintaining a kingdom’s law and order. A king could not undertake his religious, military or judicial/enforcement roles alone. An Anglo-Saxon king could not be authoritarian and survive to be successful. He needed the active support of the Church, his leading men – the elite of the kingdom – and ultimately, the whole community.

The monarch remained a tribe’s or kingdom’s link to the Divinity and was pivotal in drawing together physical and spiritual forces initially to form, then to protect, the kingdom. In turn, it was essential that the monarch be protected, as far as possible, in a violent world. His key role in the survival and prosperity of a kingdom placed him at high risk when enemies raided or invaded, attested by the violent ends of a number of Anglo-Saxon kings at the hands of the Vikings; for example, Saint Edmund, King of the East Angles (see the wonderful book by Francis Young).

A king had semi-divine status in pagan Anglo-Saxon society – the link between a people, their gods and their land. Many Anglo-Saxon king lists include the pagan god, Woden, as a root ancestor. Unfortunately, this can never be verified by a DNA test. A king’s linkage with the spiritual world survived the bumpy conversion to Christianity with the Church anointing the monarch as divinely chosen to rule by right. To reinforce this, a king who was martyred was destined to be made a saint – the nearest thing in the Church to a person being deified. The Church was happy to reinforce the loyalty of the community to their kings and nobles as, in a highly stratified society, this facilitated the conversion of the people, once their lord had converted.

A king’s life and authority depended on his building and sustaining relationships of active mutual trust, support and loyalty with powerful men and with the greatest warriors.

Violence was an endemic and accepted part of life in Anglo-Saxon times – not just between kingdoms but also between tribes and kin groups. In terms of aggression from beyond a kingdom’s borders, a king’s military role in war was essential. He was expected to personally lead his forces in battle. He was the personification of the kingdom. A king needed the most experienced and able warriors with him – those he could trust with his life. When kingdoms expanded, facing bigger military challenges and armies increased in size, drawing in more freemen who were less adequately trained and equipped, the existence of a kernel of experienced, loyal warriors proved their worth.

While a king was set apart, the leading men of a kingdom also had military functions and gathered around them groups of warriors who lived within their households, sharing their hearths. These magnates might be client kings in the earlier years of kingdom formation and ealdormen from the middle period onwards. Their functions included providing armed men for the king’s army and leading armies on the king’s behalf (Lambert, pp 116-18).

The leaders we see in poetry were often glorified for their personal heroism, rather than sensible, military decision-making. However, there were many kings who were strategically thoughtful and farsighted, as well as brave and inspiring. How else could they have eventually led armies to defeat the Vikings and form England from the broken kingdoms? Kings from Wessex, like Alfred the Great and his son and grandson, Edward the Elder and Athelstan, who were great leaders, in war and peace. The death in battle of one of these kings could have had a dramatic impact on the fate, not only of Wessex, but also of England.

The Anglo-Saxon Warrior

A warrior’s main role was to protect his lord and fight his battles. Loyalty to one’s lord is portrayed in poetry as outweighing loyalty to blood kin. In this, we might see the dynamic of the growing importance of kingdom-building; in extending the web of loyalties beyond family. This bond had to be built, often against the grain, and sustained. A hearth group became a warrior’s family.

A warrior without a lord was depicted as, at minimum, a sad being and, at worst, a pariah. He carried the suspicion that he had deserted his lord, leaving him to die or, worse still, had betrayed him. Such a man would not be trusted and as Pollington points out, might have powerful enemies consequent to his actions and a new lord would be reluctant to take on any existing feuds by accepting the man into his retinue (Pollington, p 103). A lordless warrior lost the benefits of a lord’s protection and patronage and the fellowship of men – but the dominant theme is the stigma of cowardice – the loss of face in a society where one’s honour and reputation were paramount.

If one’s leader was killed then the done thing, according to heroic poetry, was for a companion worthy of his name to fight on and avenge his death or die in the attempt. There was no talk of living to fight another day. To leave the field without avenging a dead lord or dying in the attempt, was simply cowardice. There is a practical side to this; a king was a battle leader and with his death went the strategic and inspirational focus of an army. His death resulted in disarray, dismay and probable slaughter. This was a powerful incentive to fight hard and not to get into an acephalous position in the first place and while not universally followed, many hearth companions would have preferred death to dishonour and misery. The Battle of Hastings, which ended the Anglo-Saxon period, is a case in point, where most of the elite and their closest followers perished.

Anglo-Saxon poetry includes didactic references contrasting how a companion should and should not behave. The Battle of Maldon, written to commemorate the battle fought in 991 AD between a Danish raiding force and the men of Essex under their ealdorman, Byrhtnoth, who was killed in the battle, includes the following memorable words:

Byrhtwold held forth, heaved up his shield – he was an aged companion – he shook his ash spear. Most courageously he enjoined the warriors:

‘Resolution must be the tougher, hearts the keener, courage must be the more as our strength grows less. Here lies our lord all hacked down, the good man in the dirt. He who now thinks of getting out of this fighting will have cause to regret it forever. I am grown old in life. I will not go away, but I mean to lie at the side of my lord, by the man so dear to me.’ (Bradley, p 527).

However, in the same struggle a few of those who had received the benefits of companionship with Byrhtnoth failed the test:

Then those who had no will to stay there made off from the conflict. The sons of Odda first took flight there; Godric took flight from the battle and deserted the good man who had often given him many a horse (Bradley, ibid., p 524).

Camaraderie is always critical to warriors. Imagine a fiercely contested battle against an army from another kingdom or against invading Vikings. A sharp blade or vicious point is inches or seconds away and could come from any of a dozen foes – hand-to-hand or whistling through the air. You haven’t got eyes in the back of your head. Your life is in the balance. Your dependence on your skills, experience and bravery – and on the support of your comrades is total.

At a time when a person’s lineage told others of the quality and bravery of one’s stock, a lesson from this Maldon text is that the courageous will live on, as their glorious feats are recounted in the halls of their people, while those who failed the standards of warriors will be named and shamed, and their conduct will impact on future generations.

Continuing with the Battle of Maldon, the incomplete surviving text of the poem contrasts with the terse reference in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for the year 991:

A 991. This year was Ipswich ravaged: and after that, very shortly, was Byrhtnoth the ealdorman slain at Maldon.

The poem has been loaded with additional meanings that are consistent with the heroic ethos. Scholars have generally interpreted the poem as depicting a moral victory of the bond between companions and their lord, despite being a military defeat. Byrhtnoth’s death and the death of many of his men is precipitated by his own actions in letting the Danes cross a causeway to fight. Whether caused through pride, arrogance, misplaced heroism or miscalculation, the loss is only redeemed by the values and loyalty of some of Byrhtnoth’s hearth companions. In a society where personal honour was critical for all freemen, it is easy to see the draw of this message.

The Battle of Maldon was fought during the reign of Aethelred ‘the Unready’ (966-1016 AD), when the image and reality of strong kingship were appearing a bit threadbare. Modern scholarship does not give the king a uniformly bad press, emphasising the challenges he faced, especially from the Vikings; however, he never surmounting them. This was a period of renewed Danish raids, vast payments of Danegeld and national disquiet. The poem appeals to timeless values of courage and loyalty that the writer may have considered to be missing in the monarch.

Some Church leaders struggled with the perpetuation of ‘pagan’ Germanic and classical warrior heroes in poetry, as these depicted non-biblical and supernatural figures, often of dubious morality. Alcuin famously complained to a bishop, ‘What has Ingeld (a legendary warrior) to do with Christ?’ The Church, which was never a single bloc of one mind, developed several approaches to the problem. One was to stand against any compromise with pre-Christian beliefs and to seek to gradually demonize anything that was not biblical. As Yorke points out, this ‘binary’ approach of delineating who and what was acceptable/unacceptable was a blunt tool. However, revolutionaries have often sought to divide the world into those who are comrades and those who are enemies and to remove any lukewarm dilution and confusion.

Another approach was to seek to accommodate some pre-Christian beliefs and practices; for example, by transforming some mythological heroes into ancestral human heroes with recognizable Christ-like characteristics (Yorke, pp 59-64). This was part of a strategy to attract converts, consistent with Pope Gregory the Great‘s advice to Saint Augustine of Canterbury. As Yorke says:

Wherever these (pre-Christian) beings may have come from, they have been transformed into ancestral heroes in the written genealogical tradition created for the Anglo-Saxon courts. This was part of what proved to be a somewhat controversial pact that helped ensure the conversion of the royal houses (Yorke, p 59)

That this pact was needed shows the power of the pre-Christian warrior ethos and its collection of values and esteemed behaviours, especially amongst the elite.

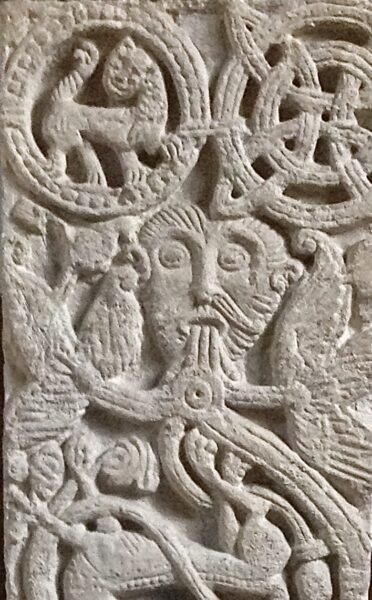

The heroic warrior ‘props’ in Anglo-Saxon poetry have received significant archaeological corroboration, most notably, of course, from royal and warrior burials. Most spectacularly, the Sutton Hoo ship burial in East Anglia, initially excavated on the eve of WWII, brought to mind the ship burial of Scyld Scefing from the greatest Anglo-Saxon poem – Beowulf (Newton, pp 135-142). Warrior helmets have also been discovered, including the evocative helmet and face mask from Sutton Hoo, as well as from Benty Grange (Derbyshire) and Coppergate (York). Wonderful ‘pattern-welded’ swords – clearly treasured warrior possessions – have also been found.

The historical context of the bond between king and hearth companion obviously changed. Although the image was undoubtedly gilded by heroic poetry, the inescapable fact is that the quality of Anglo-Saxon forces and leadership under the Kings of Wessex had become sufficiently formidable to fight off invaders and form England over the period from about 870 to 940 AD. They must have been doing something right. The Anglo-Saxons almost pulled it off in the end and 1066 was a close run thing. The result may have been different if King Harold had not needed to march to Stamford Bridge near York for one battle then return south to fight Duke William.

The Gift

The concept of the gift is fascinating anthropologically. In his famous book of 1925, The Gift (2002), Marcel Mauss argued that in many early societies, the gift functioned to generate reciprocal obligations and thus both to bind together social groups and reinforce hierarchies. Accordingly, a ‘gift’ is often a misnomer. It is not given always without expectation of benefit but, on the contrary, to create obligations. If a person chose to refuse a gift, they were refusing the relationship it embodied. Gift-giving had a ritual and spiritual dimension, as well as material. The acts of giving and receiving were often accompanied by ritualised speeches, generating a sense of magical, spiritual behaviour (Pollington, pp 43-45). Thus, an Anglo-Saxon lord would give gifts to his companions in return for their past and future loyalty and acts of service and bravery. Indeed, the term, ‘ring-giver’, refers to a lord.

A gift could be a time-honoured heirloom but more often than not it was part of the booty from war, which could be a profitable business. A cynic could suggest that gift-giving was simply distributing what was owed to warriors for their part in a venture but this would be a stark economists’ analysis – only partly true. However, a lord who was parsimonious in gift-giving would soon lose the loyalty of his chosen men and gain an unpleasant reputation.

Anglo-Saxon poetic references to gift-giving reflect its importance, as in Beowulf:

Then the protecting lord of earls, the king renowned in warfare, commanded a gold-decorated blade, a legacy from Hrethel, to be fetched in – at the time there was no finer treasure among the Geats in the category of the sword. This he laid in Beowulf’s lap, and granted him seven thousand hides of land, a hall and a prince’s throne. (Beowulf, in Bradley, p 469).

And for one of the greatest Anglo-Saxon kings, Athelstan:

Here King Athelstan – the lord of heroes,

The warriors’ ring-giver …. (Battle of Brunanburh, in Pollington, p 258).

The Hearth

The hearth conjures up images of warmth, feasting, comfort and light surrounded by darkness, danger, the unknown and demons. It was the heart of the hall, where the songs and poems of a people were sung and recited. In Anglo-Saxon poetry, the hearth stands for all of these delights, domestic and communal, and reinforces the theme of companionship. It’s a wonderful image of human solace in the face of the dark unknown and danger. As Bede recounts what one of King Edwin of Northumbria’s chief men says when discussing whether to accept Christianity:

…it seems to me like the swift flight of a single sparrow through the banqueting-hall where you are sitting at dinner on a winter’s day with your thanes and counsellors. In the midst there is a comforting fire to warm the hall; outside, the storms of winter rain or snow are raging. This sparrow flies swiftly in through one door of the hall, and out through another. While he is inside, he is safe from the winter’s storms; but after a few moments of comfort, he vanishes from sight into the wintry world from which he came. Even so, man appears on earth for a little while; but of what went before this life or of what follows, we know nothing. (Sherley-Price, p 127).

Hall interior at the wonderful Anglo-Saxon reconstructed village of West Stow, at the site of the original settlement

When most buildings were wooden, the hearth was one of the few structures made of stone; giving it a greater permanence. We can imagine that until the wide availability of electricity, the hearth remained the focus of life after sundown for most of humanity for countless generations. It is a time-honoured, deeply evocative image.

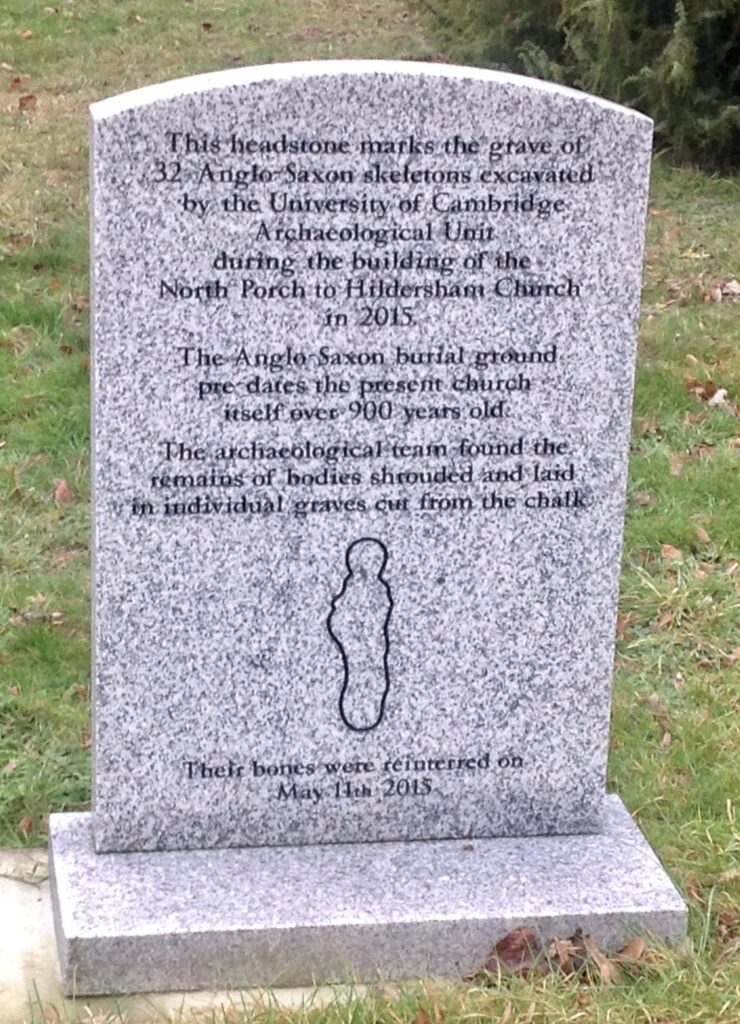

The Grave

The hearth with its solace and companionship does not last. We come inevitably to the end of life, whether by violence, sickness or old age for those fortunate to have lived through childbirth and childhood. It is impossible to read Anglo-Saxon poetry without feeling a sense of melancholy. The grave was never far away, especially for warriors. Warriors are killed or lose those they have grown close to. The inevitable end, in the mind and in the flesh, gave poignancy to the joys of companionship and the hearth. But what happens after death?

The pre-Christian view of what’s in store for the dead was not dreadful. Courageous, honourable warriors spent a lot of the afterlife feasting. In many ways, the dead had not left the building. The spirits of the dead could still be contacted, especially at their grave sites and other special places in the landscape. The durability of landscape features reinforced the conservatism of the warrior elite and these sites remained religious/political/social bastions of pre-Christian belief and practice among warriors for many generations during and after the conversion period. Often great aristocratic heroes were accorded burial at auspicious, prominent sites, as with Beowulf’s ashes.

Then the Weder-Geatish people built a resting-place on the headland, which was high and broad and widely visible to those journeying the ocean… (Bradley, p 494).

So, is the melancholy we sense in Anglo-Saxon heroic poetry more an emotion generated by the Christian afterlife, or is it something instilled by pre-Christian beliefs that held on tenaciously? Or is it something that depends on a warrior’s career. An heroic, honourable warrior might feel happier with his fate in the pagan afterlife than in Heaven? It was certainly an uphill battle for the Church during the conversion period to persuade folk to accept unfamiliar, unpalatable elements of Christianity, including that once dead, the soul leaves and has nothing more to do with the living. The evidence shows that the conservatism of the courts and warrior elite necessitated an awkward compromise from the Church. Some scholars also consider that a response from the elite to attempted conversion was to become more conspicuous in their paganism. In addressing burial mounds, Carver employs the terms, ‘reactive monumentality’ and ‘defiant paganism’ (Carver, 2010, p:9).

So, did Christianity, including its view of death, affect the dynamics of leader and hearth companions? Surely it did but slowly, inconsistently and probably superficially for a long period. We should remember that the eschatological perspective of Christianity is found in all surviving Anglo-Saxon heroic poetry, as this was written during or after the conversion to Christianity. However, heroic poetry is an amalgam of pre-Christian and Christian themes, as with much Anglo-Saxon thought and culture, especially during the lengthy conversion period.

What would this mean in practice? While some leaders of the Church would have found explicit ‘pagan’ aspects repugnant; on-the-ground, there was more of an acceptance of obdurate aspects of pre-Christian practice and belief by the warrior class.

Kings and their leading councillors began to accept and indeed embrace aspects of Christianity, especially those that were practically beneficial and some of this impacted on the relationship between king and hearth companions and its depiction in poetry. Kings were cloaked with the mantle of sacred authority under God. Old Testament models of kingship were absorbed. The Christian Deity came to be seen as the ultimate Lord and the transitory nature of life and beyond death, the promise of eternity, slowly took hold.

The new beliefs are summed up well in the poignant Anglo-Saxon poem, The Wanderer:

The whole kingdom of earth is full of hardship; the dispensation of fate makes mutable the world below the heavens. Here wealth is ephemeral; here a friend is ephemeral; here man is ephemeral; here kinsman is ephemeral; all this foundation of earth will become desolate…. It will be well for him who seeks grace, consolation from the Father in heaven, where for us all the immutable abides (from The Wanderer, Bradley, p 325).

Bradley comments: ‘So in The Wanderer; it is clear that the wanderer will not find on earth the lord he needs, and the journey homewards to which his yearnings impel him is finally understood to be the journey of life towards death and eternity beyond (Bradley, p 322).

Anglo-Saxon High Status Bromances?

So, what are we to make of the image of the Anglo-Saxon leader and his hearth companions? Undoubtedly, heroic poetry glorified war, the warrior aristocracy and their way of life, which was indulgent. It perpetuated elements of pre-Christian culture and belief but gave it all a sort of Christian coat of paint – and sometimes the two traditions blended and sometimes they struggled. Is it akin to medieval notions of chivalry – a nice, poetic ideal, rarely practiced and indeed, a smokescreen for brutality?

But the images are not simply fictitious, high status bromances that mask the vicious nature of Anglo-Saxon militarism and the chasm between the elite and common folk. They are more than crude ruling class ideology. In a period of warfare between kingdoms and the threat and reality of invasions, a strong, loyal warrior class, facing the probability of a short life, was essential.

Anglo-Saxon kings were the heart of the kingdom with semi-divine status. Together with other noble leaders, they surrounded themselves with trusted warriors, mainly from the aristocracy but also others selected for their martial qualities. It made good sense. The chosen warriors would have trained and spent much time together, learning to fight cooperatively. They were fortunate to be able to eat and drink their fill but physically weak warriors were not going to last the distance in a battle – the common soldier certainly had a brutal time. They shared common values and an esprit de corps developed. This was essential in developing a viable force to defend the kingdoms. What started as a household guard developed over the Anglo-Saxon period into a fighting force that proved to be very effective.

The relationship between a leader and his hearth group in Anglo-Saxon society was sustained by training in a lord’s household, shared dangers, companionship, gift-giving, patronage and the inspiration of heroic poetry. The feats and qualities of great heroes were recited and extolled in these poems, where one’s own courage could also be commemorated.

Heroic poetry was part of the elite’s subjective autobiography – evocative, rose-tinted, conservative with a splash of Christianity added later – but it also celebrated and motivated a relationship that was central to the defence of the kingdom and to the creation of England.

(All photos taken by author).

Bradley, S. A. J., (ed.) Anglo-Saxon Poetry, Dent, London, 1982.

British Library, Athelred the Unready, https://www.bl.uk/people/aethelred-the-unready

Lambert, T., Law & Order in Anglo-Saxon England, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2017.

Mauss, M., The Gift, Routledge Classics, London & New York, 2002.

Newton, S., The Origins of Beowulf and the Pre-Viking Kingdom of East Anglia, D.S. Brewer, Cambridge, 1994.

Pollington, S., The English Warrior from Earliest Times till 1066, Anglo-Saxon Books, Frithgarth, 2002.

Sherley-Price, L., (translator) Bede, A History of the English Church and People, Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1968.

Yorke, B., King Alfred and Weland: Tradition and Transformation at the Court of King Alfred, in Transformation in Anglo-Saxon Culture, edited by C. Insley and G.R. Owen-Crocker, Oxbow Books, Oxford, 2017.

Young, F., Edmund, In Search of England’s Lost King, I. B. Tauris, London, 2018.

Pingback: Mystical Life in Anglo-Saxon England – Conversion – Father Eadred

Pingback: Anglo-Saxon Saints - Piety and Compromise - Father Eadred

Pingback: Anglo-Saxon Monastic Decay - Father Eadred