Part One: ‘Pagan’ Spiritual Beliefs

If I were to venture a breathtakingly broad generalization of the spiritual history of the Anglo-Saxons, I would use the metaphor of a giant interconnected system of rivers and streams with ‘pagan’ (i.e. non-Christian) and some Christian waters intermingling with tolerance and little impediment up to the Conversion period. From 597 onwards, the Roman Church tried to channel and dam this system, and to increasingly differentiate pagan from Christian. The Church was content for a time to let some obdurate streams retain their traditional courses, but they recast these as Christian. By whatever method, the Church worked to end the influence of paganism and to replace it. At one level, it eventually succeeded. However, there were individual streams from the pagan past that continued to evade the Church’s efforts. Moreover, the giant mainstream Christian river that flowed chaotically on towards the Norman Conquest would never be free of water from pre-Christian springs – it would be coloured in surprising ways by pagan beliefs and practices.

In researching for my latest novel, Murder at Elmstow Minster: A Father Eadred Tale, I waded into these waters to try to understand more about the mystical life of the Anglo-Saxons. Part One of this series is about Anglo-Saxon ‘pagan’ beliefs. Part Two looks at what conversion to Christianity might actually have meant. Part Three looks at the spiritual charge of saints, royalty and the landscape. Part Four covers Church organisation. Together, they give a flavour of the religious environment in which Eadred the priest lived.

It is vital that we do not over-rationalize Anglo-Saxon spirituality and conversion to Christianity. If we look solely through secular 21st century eyes, we risk simply reflecting our own mental frameworks. I would therefore ask readers of this article and my novel to assume the existence of the spirit world, even if you do not believe it, and not to separate the sacred and the secular.

The Anglo-Saxons, whether pagan or Christian, were a deeply spiritual people. As an Anglo-Saxon, I would expect to have many encounters with spiritual beings and otherworld creatures, benign and malevolent. Various deities, ancestors, ghosts, witches, giants, dwarves, elves, animal spirits, spirits in trees, forests and rivers, shapeshifters, monsters, dragons and many more could be part of my world. They were joined later by the Holy Trinity, angels, saints and demons.

‘… the every day life of the people took place in a theatre which was also occupied by spirits, benign, malevolent and ancestral’ (Semple, S., 2010: p 43).

Gods

The evidence of pagan Anglo-Saxon spirituality is thin but most scholars draw analogies with Norse religion and draw out three strands: the cult of the gods, animism (belief in the existence of spirits, including ancestors) and magic (Sanmark, A., 2004: pp147-50, in Sanmark, A., 2010: p160).

The evidence for Anglo-Saxon pagan gods is spread sparsely across several fields, especially archaeology and the names of places and times. Thus, Easter is named after Eostre, the Anglo-Saxon goddess of spring. Tuesday is named after the god, Tiw; Wednesday named after the god, Woden; Thursday after the god, Thor; and Friday after the goddess, Frig. There are also many place names derived from links to deities, such as Thursford in Norfolk (Thor), Wednesbury in Staffordshire (Woden) and Frathorpe in Yorkshire (Frig). Particular landscape features were also dedicated to various deities, as well as to long-forgotten spirits.

The genealogies of several of the ruling dynasties of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms also name pagan gods, especially Woden, in their mythical past. Some scholars see this as a reaction of the conservative elite wanting to highlight their ambivalence or antagonism towards the spread of Christianity.

The relationship of kings and gods in the pagan world was to have a massive impact on conversion. When Christian missionaries entered the Anglo-Saxon pagan kingdoms, they became aware that kings possessed both temporal and religious authority. It was this sacred link between gods, people and the land that royalty embodied, a link between the observed and spiritual worlds, that led the Church to seek first the conversion of the royal elites (Urbanczyk, P., 2005: p20). More on this in Part Two.

It is clear that gods played an important part in pre-Christian belief. However, it also appears that the cult of the gods disappeared, at least on the surface, soon after the ‘official’ introduction of Christianity, drawing on the experience of Iceland and Scandinavia (Sanmark, A., 2004: chapter 4.1, in Sanmark, A., 2010: p159). We can assume without much imagination that veneration of familiar gods went underground, as the Church and state preached and legislated increasingly against open polytheism. As we shall see next, belief in spirits proved far more durable.

Spirits

It appears probable that spirits, especially of the ancestors, had far greater impact on the lives of ordinary people than gods, and were less visible to the clergy. Spirits were a complex tribe. They could live in landscape features, manifest as animals and birds, change shape, and live on as the souls of ancestors. They tended to be localised and live in distinctive parts of the landscape – features that stood out from their surroundings (hilltops, groves) or in features that were liminal, bordering two states of being, such as springs, rivers, meres and caves. Existing enclosures, tombs and other strange man-made edifices from the distant past were also considered to be the homes of spirits, as these sites embodied the magic of past lives.

Trees were also a favoured haunt of spirits and special trees had sacred importance. The world-tree was central to pagan spirituality:

‘The world-tree is considered a key and common element of pan-northern European, pre-Christian belief, indeed it is an almost universal element in world religion’ (Russell, 1979, in Semple, 2010: p41).

Nick Mayhew-Smith makes an interesting point about the apparent lack of destruction of sacred trees by the evangelizing Church in England – unlike experience on the Continent. He sees this in part as the result of such living beacons being recognized as a ‘neutral negotiation space’ between potential adversaries. Not just because of their convenience but due to traditional, widespread recognition of their spiritual power (Mayhew-Smith, N., 2019: p22).

The landscape was sacred; a timeless place where those within the spiritual world could be contacted at specific locations; where the ingredients for magic potions could be obtained; and where rituals were performed. This included the domesticated side of the landscape with its seasonal agricultural rhythm, as well as the wilder realm.

‘The natural world was fundamental to pre-Christian and post-Conversion popular beliefs’ (Semple, 2010: p21).

The central role of the natural world to pagan beliefs required it to undergo its own conversion at the hands of the Church, so that sites of pagan significance were gradually reassigned either to the Deity or a saint, or damned. More on this in Part Two.

The natural world also included animals, wild and domesticated. It is generally agreed that depictions of certain belligerent animals on military equipment were not just a metaphor for the ferocity of the wearer but had spiritual significance – the animal’s spirit defended the wearer and attacked his opponent in the spirit world. The best example is the boar.

Pluskowski comments on the use of a boar on helmet crests in seventh century England and Scandinavia, and quotes from Beowulf:

‘… the weapon-smith wrought it thus, worked it with magic

set it with swine shapes so that thereafter no

blade nor battle sword might bite through…’ (Pluskowski, A., 2010: p113).

Pluskowski also refers to the arguments of Glosecki and Williams in support of an animistic pagan Anglo-Saxon society, where the spiritual was accessible through the natural (Pluskowski, ibid: p116). Another example is the wolf. The Wuffingas were the royal dynasty of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of the East Angles. Their family name means, ‘kin of the wolf’. Sam Newton believes this name indicates a totemic/guardian spirit link between the wolf and the East Anglian royal dynasty. He interprets the story from Christian times of a great wolf protecting the severed head of the last Anglo-Saxon king of the East Angles, St Edmund, killed by the Vikings, as deriving from the traditional association of the wolf with the dynasty (Newton, S., 1993: pp106, 109).

Ancestors and the Soul

To the pagan mind, ancestors had not left the building; they lived on through their soul and were accessible to the living. The relationship of the living to their ancestors was much the same as to a more senior, well-loved, demanding member of the family and with a healthy dose of fear. Ancestors could, however, provide supernatural assistance to their living kin. Certainly, pagan Anglo-Saxons did not have a pessimistic view of the afterlife.

The pagan view of the soul was complex, often conceived as a duality of a ‘breath’ or body soul and a ‘free’ or dream soul. While the body breathes, the free soul can become active and leave the body in dreams and trances; and once the person dies, it takes them into the next life. The soul could also shapeshift into an animal, and as one, it may visit the ancestors (Sanmark, A., 2010: pp160-163).

Shapeshifting between a human and an animal form was far more than a party trick to the pagan Anglo-Saxons. It expressed a relationship between humanity and nature that most of us today cannot comprehend. It also expressed a relationship between the every-day and spiritual worlds, between the body and the soul that has long since left the mainstream Western world. Brian Bates, in his book, The Real Middle Earth, about magic and mystery in the Anglo-Saxon world – a world that they termed, Middle Earth, sums up these relationships:

‘The essence of the Middle-earth view is that the physical shape of a creature is only one aspect of it, and not its defining feature. Soul has fluency and energy which can be expressed in other forms. And there was an interflow between the soul forms of people and of other animals. This is the source of the intimate connections people felt with animals in Middle-earth’ (Bates, B., 2003: p164).

Magic

Magic is another of those concepts that has been pushed to the margins of modern Western thought and practice. It was not so with pagan – and indeed, many Christian – Anglo-Saxons before, during and beyond the conversion period.

So, what was magic? A neat definition is not possible and, as with spirits, shapeshifters and their ilk, everyday pagans and the organised Church had different takes and definitions for what it meant. More on this in Part Two. And where the educated may have seen shades of difference, an ordinary Anglo-Saxon would probably have seen none. With these caveats in mind, the simplest differentiation was between gaining benefits from the hidden or deeper powers within nature, and soliciting support from gods and spirits, generally to cause harm to others. We can see immediately that magic was an integral part of pagan belief.

Understanding the powers of nature, such as the healing benefits of plants, is often associated with ‘cunning folk’, mainly women, who became skilled in applying herbal remedies. From our eyes, it is ‘natural’, as opposed to ‘supernatural’ but Anglo-Saxons did not see it like this. A cunning woman might invoke the help of a spirit and perform a ritual while preparing a natural remedy.

So, is pagan magic simply an indistinguishable part of pagan belief in calling on spiritual beings for help, with the definition of ‘magic’ being something that the Church devised later? Kieckhefer argues that the Church did indeed introduce a distinction between magic, which was the work of demons, and miracles, which was the work of God (Kieckhefer, R., 2000: p.35). However, he also believes that pagans would make a differentiation – between openly venerating gods and spirits and calling on their positive support, and secretly seeking their help to cause harm within the community. Both involved calling on gods and spirits but magic had the additional characteristics of being covert and seeking harm to other individuals:

‘The pagans did not care what gods you venerated, so long as you did so openly and did not call on them for help in performing evil. If you did invoke the gods’ help for evil, what you were doing was both religious and magical; the realms were not distinct, since magic relied on aid and instruction from the gods’ (Kieckhefer, R., ibid. : p37).

The argument that calling on spiritual powers to cause harm was anathema to pagans, as well as Christians, aligns well with the view that secret forms of wrongdoing, such as theft, were particularly problematic to Anglo-Saxons, irrespective of their religious belief, because they caused widespread harm. Not only did secret crimes harm the directly affected individuals but they sowed suspicion and damaged all-important community cohesion (Lambert, T., 2017: pp99-102).

Conclusion

The pre-Christian Anglo-Saxons were blissfully polytheistic with a panoply of gods and spirits; many of whom were local, personal and ancestral. There was little hint of attempts to control beliefs or impose uniformity. This continued the spiritual environment of the preceding Celtic and Roman periods. The natural world, including the landscape and animals, provided links to the spiritual realm and furnished ingredients for magical potions etc. Ancestor cults expressed the continued life of the soul and were of great significance in the practical lives of the people, as they had been for generations. While magic invoked support from the spiritual world, its use to harm individuals and communities was condemned.

Polytheism, animism, ancestors, magic, territorial variation, and the complex relationship between people and animals were areas of certain conflict with evangelical Christian missionaries. Part Two of this series looks at the complicated spiritual, political and cultural processes involved in the conversion to Christianity.

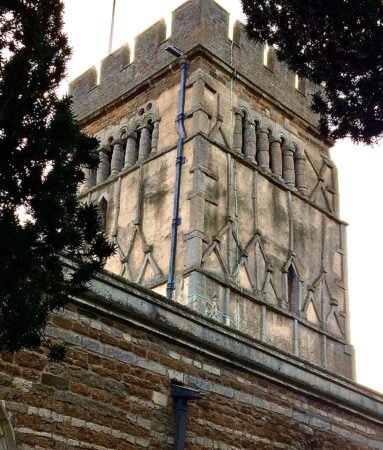

(All photos by author)

References

Bates. B. (2003) The Real Middle Earth, Magic and Mystery in the Dark Ages, London, Pan.

Kieckhefer, R. (2000) Magic in the Middle Ages, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Lambert, T. (2017) Law and Order in Anglo-Saxon England, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Mayhew-Smith, N. (2019) The Naked Hermit, A Journey to the Heart of Celtic Britain, London, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

Newton, S. (1993) The Origins of Beowulf and the Pre-Viking Kingdom of East Anglia, Cambridge, D.S. Brewer.

Pluskowski, A. (2010) Animal Magic, in Carver, M., Sanmark, A. and Semple, S. (eds.), Signals of Belief in Early England: Anglo-Saxon Paganism Revisited, Oxford, Oxbow Books.

Russell, C. (1979) The Tree as a Kingship Symbol, Folklore, 90: 2: pp217-33.

Sanmark, A. (2010) Living On: Ancestors and the Soul, in Carver, M., Sanmark, A. and Semple, S. (eds.), Signals of Belief in Early England: Anglo-Saxon Paganism Revisited, Oxford, Oxbow Books.

Sanmark, A. (2004) Power and Conversion, A Comparative Study of Christianization in Scandinavia, Opia 34, Uppsala, Uppsala University Press.

Semple, S. (2010) In the Open Air, in Carver, M., Sanmark, A. and Semple, S. (eds.), Signals of Belief in Early England: Anglo-Saxon Paganism Revisited, Oxford, Oxbow Books.

Urbanczyk, P. (2005) The Politics of Conversion in North Central Europe, in Carver, M. (ed.), The Cross Goes North, Processes of Conversion in Northern Europe, AD 300-1300, Woodbridge, The Boydell Press.

Excellent summary, I think this is a completely plausible picture when it comes to describing the diffuse spirituality of the early church in Britain. It’s clearly written too, which is another bonus when it comes to shedding light on a difficult period to understand.

Trees definitely play a large part in the conversion of the folk people to Christianity, and it’s interesting to note just how much the ‘Celtic’ and the Anglo-Saxon missionaries saints have in common on this point. There are plenty of stories of a saint (Celtic and A-S alike) going to a location and planting their staff, which miraculously grows into a mighty sacred tree. That is obviously a backwards explanation for why so many early churches are situated right next to a sacred tree. The idea that the first missionaries took the practical decision to simply adopt an existing tribal tree might have been a bit embarrassing to the later church, so they came up with this ingenious explanation. So that indicates there was a degree of compromise going on. Great stuff, Lindsay.

Thank you, Nick, for your comments and kind words. I found your book full of insights on Celtic spirituality and the early church in Britain, and the creative interaction of beliefs in that period. That interaction was one of the characteristics that make the Anglo-Saxon period so interesting in terms of beliefs. As always, there was a tension between folk belief and Church regulation (my next article) but that great sense in Britain of spiritual continuity was one of the legacies. Looking forward to your next book! Thank you, Lindsay

Pingback: Mystical Life in Anglo-Saxon England – Conversion – Father Eadred

Pingback: Anglo-Saxon Saints - Piety and Compromise - Father Eadred

Pingback: Anglo-Saxon Monastic Decay - Father Eadred

Pingback: When and why did the Anglo-Saxons build with stone?

Pingback: The Fenland Spell - An Anglo-Saxon Murder Mystery - Father Eadred